New Jersey Member Discovers His Ancestor’s Original Membership Certificate Signed by George Washington

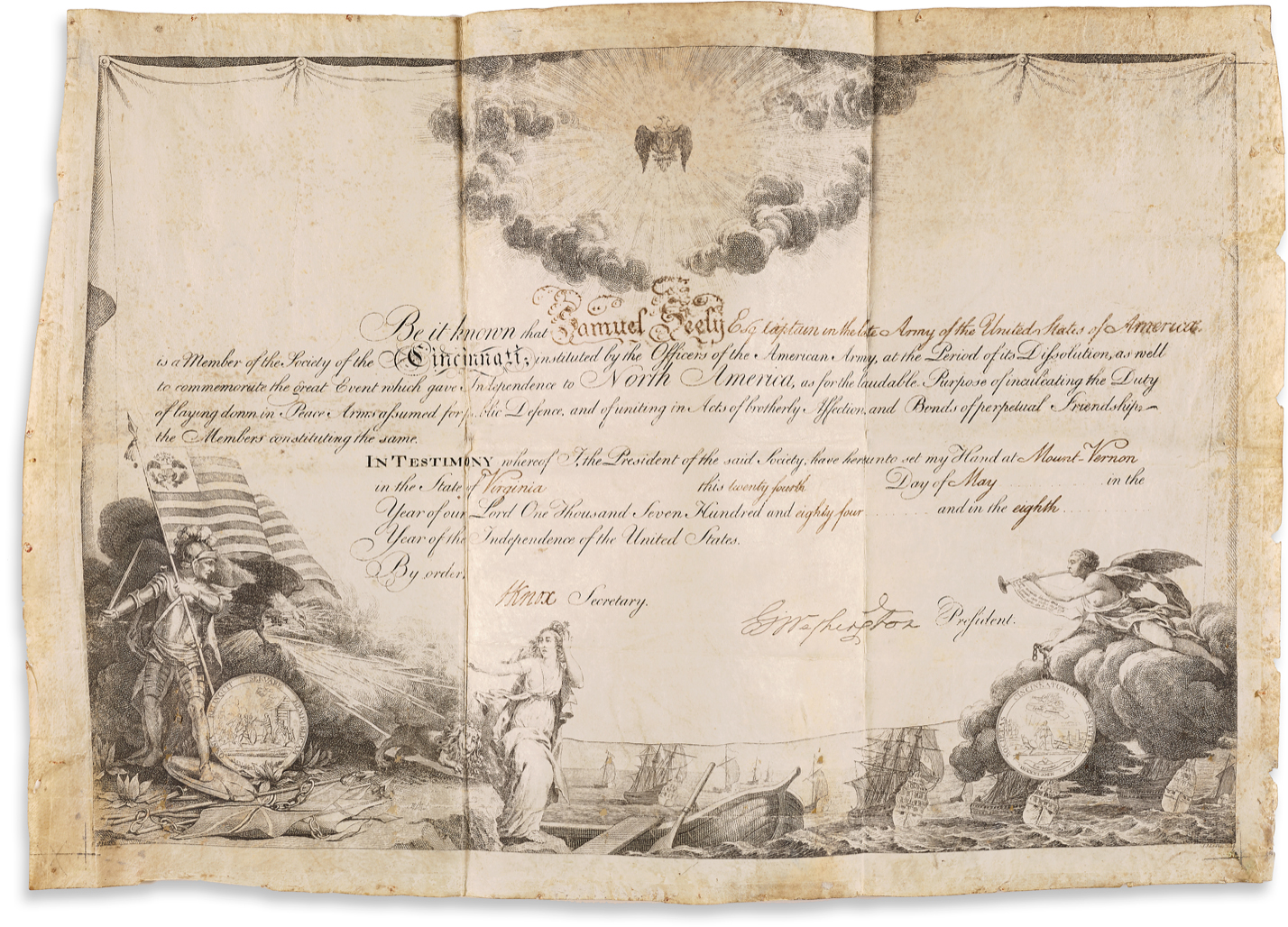

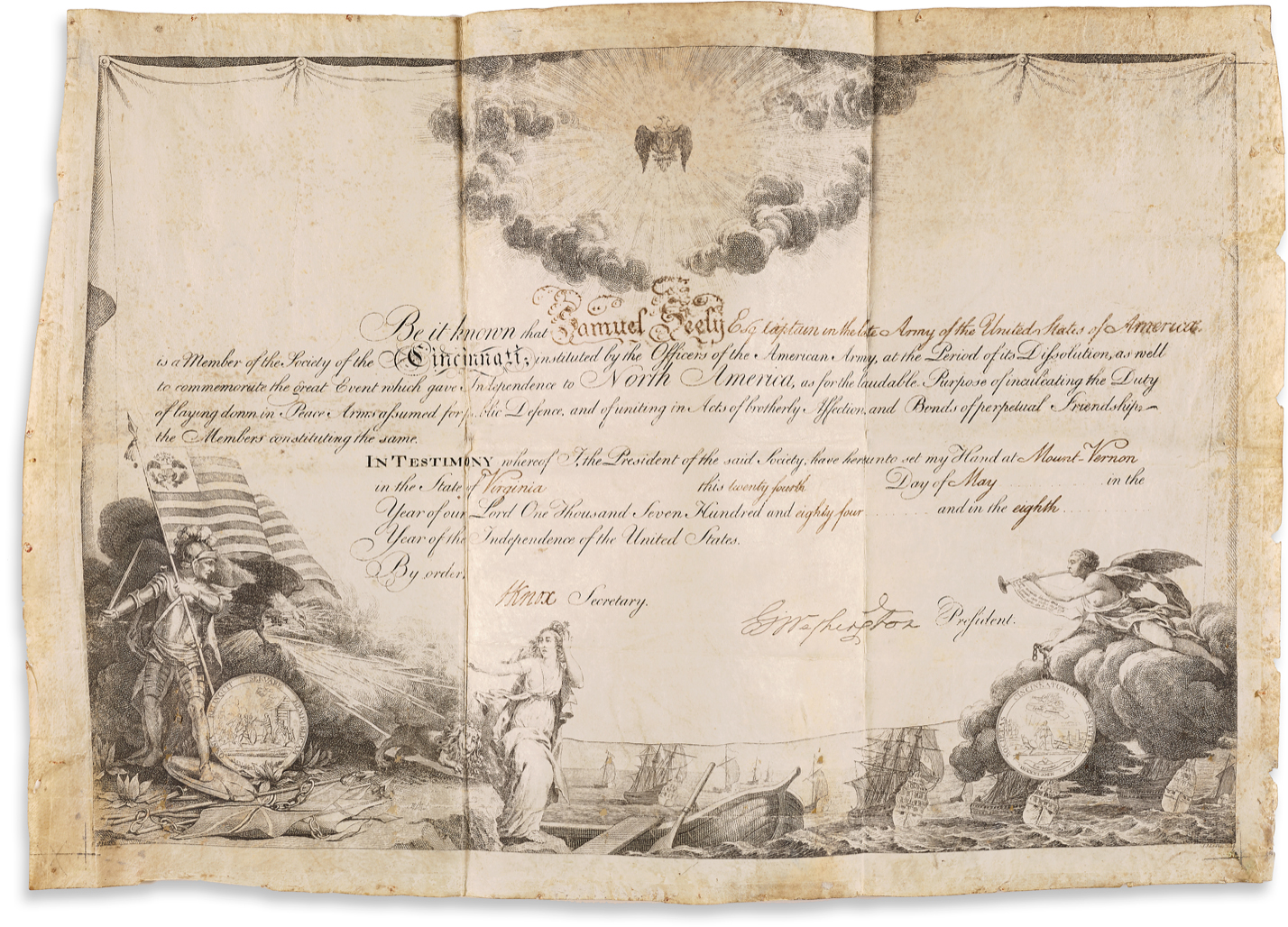

A digitally enhanced scan of the Society of the Cincinnati Membership Certificate belonging to Captain Samuel C. Seely

One of the most valued possessions of any member of the Society of the Cincinnati is their Membership Certificate. Designed by Pierre Charles L’Enfant (an original member of the Society remembered largely today for laying out the new nation’s capitol: Washington, D.C.) and engraved by Jacque LeVeau on parchment, the first certificates were signed by the Society’s first President-General, George Washington, as well as Secretary Henry Knox.

Such highly sought-after autographs make these early certificates especially valuable, and it is not unusual to see them sell for $25,000 or more at auction. Many have found their way into museums, such as the Society’s own museum in Washington, D.C., which possesses several, while others have remained in the family of their original owner, being passed down, like the Society’s membership, from one descendant to the next.

Recently, Ed Lary was admitted to the Society of the Cincinnati in the State of New Jersey as the representative of Samuel C. Seely, one of the original members of the Society, who had earned membership by serving for over five years as a commissioned officer in the Continental Army.

Unlike some fortunate members, Lary did not inherit his relative’s diploma. But, he did happen to know exactly where it was.

But how did such a precious and treasured heirloom end up in the possession of the National Archives? The answer to the question is closely bound to one of the core reasons the Society was founded. For it was submitted to the courts by Seely’s widow, Patience, in 1838 in order to prove his service, and thus qualify for the recently enacted pension for widows.

Silhouette of Samuel C. Seely

Tragically, though Seely himself lived until 1819, thirty-six years after the conclusion of the American Revolution, he did not live long enough to enjoy the fruits of a pension act passed by Congress only the year before his death. Often railing against the government’s inaction, the Society of the Cincinnati took matters into its own hands when possible, dispersing funds to veterans, widows, and other dependents, including $50 to Seely himself, in 1814, “to be appropriated in clothing for his use”. Following his death, the Society sent an annual donation to his widow for the remainder of her life.

The depth of Seely’s plight is well known to Lary, who explains “Captain Seely was destitute some years before his death, lost all of his property in NJ, and had to move in with his son-in-law Judge Dingman. His wife, presumably also destitute after his death, must have moved to Brooklyn, NY to live with her daughter Cornelia, who married Paschal Wells. She was living in Brooklyn when she applied for the Widows Pension.”

The certificate was not returned, but rather added to the widow’s pension file, and transferred to Washington, D.C. But it did not stay there.

- In 1903, it was moved for safe-keeping to a safe in the room of the Chief of the Old War and Navy Division.

- In 1904, it spent April through December in St. Louis, where it was showcased as part of the Louisiana Purchase Exposition.

- Five years later, it made its way to the Seattle Exposition.

- It took a break at that point before being sent to the Sesquicentennial celebrations in the City of Philadelphia in May of 1926.

- Then, the certificate returned to Washington, never to be viewed by the public again.

Seely’s first hereditary representative, Irving Caywood Hanners, and Honorary Member, U.S. Senator W. Warren Barbour

Since Captain Seely’s death, he had not been represented in the Society. That is, until 1936, when his great-great-great grandson Irving Caywood Hanners was elected his representative. A prominent man, Hanners enlisted the aid of friend, Senator, and fellow member, Senator W. Warren Barbour to see if he could get possession of the certificate.

“The file contained a very well-written response,” says Lary, “explaining why Irving C. Hanners’ request for release of the certificate was being denied. It said, in part, ‘To withdraw, for the benefit of one individual or descendant, parts of those [Pension File] records from the Government archives would destroy the value of the whole record at the expense of future research workers and other descendants with equal right to make claim.'”

However, the records did include a photograph of the certificate, albeit a very low quality one. Lary recalls taking a print of the old certificate photo to a digital imaging company.

“I wanted to see if we could at least print a reasonably clear copy of the certificate for my own records. The answer was no; the quality of the photo was too poor to work with.”

Undaunted, Lary decided to submit a research inquiry to the National Archives via their website. He was not especially optimistic.

“I knew that access to the certificate was unlikely, and that even finding the document’s location within the National Archives, whose location was last known 77 years ago, was highly unlikely. Quite frankly, I expected no timely reply, and if any reply, one saying that the certificate could not be found.”

But nine days later, Lary was pleasantly surprised to receive an email reply from an archivist.

Samuel C. Seely’s current representative, John Edward Lary

“She regretted the condition of Capt Seely’s Certificate, printed on parchment, prevented access by researchers for viewing. However, she had the front and back of the certificate scanned as high-resolution JPEGs and offered to mail them to me on a CD at no charge. What an incredible find!”

And while it might not be quite as satisfying as possessing the original certificate of the man who he represents in the Society, the quality of the scan, along with subsequent digital enhancements to restore some of the faded writing, have made it possible for Lary to have a high-quality printed replica while knowing the original document is safely preserved.

More than anything else, Lary states that the experience has only helped to underscore a deep sense of sadness for the Patriot he represents in the Society, as well as countless others.

“When you read these Patriots’ Pension File Testimonies, over and over again you are overwhelmed by the abject poverty these Patriots endured after the war. I suppose they were mostly farmers, and once age prevented them from working the farm, they had nothing but land and no way to generate any income; so they soon had to sell the land and other personal property to pay for taxes and expenses, and then they were left with nothing. Very sad.”